***IF READING ON A SMARTPHONE USE “LANDSCAPE” FORMAT FOR BEST RESULTS***

Graphic artist Thomas Reynolds’ work may not be evident when you listen to Necropolis, but his drawings are a critical element in our band’s DNA.

Like most groups, we had a circle of friends who were devoted supporters of the group. Thomas not only supported the band’s evolution from the earliest days, but his artistic contributions cannot be overstated.

Necropolis built its reputation on the songs and live performance, while Reynolds’ spectacular artwork helped promote and legitimize the band from the beginning.

Although the Necro-soldier was conceptually defined by the lyrics to the theme song “Necropolis”, and the evolution of the character continued through lyrics to other songs like “Biomechanix”, the visual representation was born out of Thomas’ fertile imagination. His seemingly endless creativity and raw artistic gifts were with him from the earliest days.

I first met Thom in the sixth grade, where we bonded over our drawings inspired by the recently released Star Wars sequel, the Empire Strikes Back. We were very good friends from that point on, sharing an interest in comic books, film, and of course, music.

I first met Thom in the sixth grade, where we bonded over our drawings inspired by the recently released Star Wars sequel, the Empire Strikes Back. We were very good friends from that point on, sharing an interest in comic books, film, and of course, music.

Thom was always pushing me out of my comfort zones.

When we met, I didn't read superhero comics, I'd given them up. But Thom got me to read the X-Men. And I loved it.

Being a devoted Marvel-Zombie, I dismissed DC comics.

Thom had me read The New Teen Titans. And I loved it.

He also taught me to pay attention to the names in the credits of each issue. I had noticed that I liked some artists work more than others, but I never bothered to pay attention to the names of the people responsible for the stories and artwork that I favored. Once I did, I began seeking more work that strayed from the safety of the familiar.

Thom was always open to new styles and approaches. Many times he would drag me screaming and kicking to a comic that I had dismissed outright for its unconventional appearance, and nearly every time I would discover a new favorite.

Meanwhile I had my growing library of music to share with him. We were exploring Heavy Metal, Punk and Hip Hop circa 1981-83 and digging deeper and deeper into a plethora of new sounds. We drove each other to embrace the unfamiliar and we supported each other's forays into previously uncharted areas.

This adventurous exploration led us further away from our schoolwork, until we started to avoid school altogether. At first, we would walk into East Liberty to hit up a news stand for some fresh reading material and play some video games. Then grab a slice at Vento's Pizza before finally going into Reizenstein Middle School about as late as we could without needing a note.

Such a bad influence on each other were we, that three years into our friendship, we had to repeat eighth grade for skipping too much school. That year of “independent study” pretty much determined the trajectory of our adult lives, as both of us eschewed a conventional path to the professional world, instead devoting ourselves to a lifelong dalliance with underground culture and art.

In 1984 when it was time to go on to high school, the “powers that be” made sure we didn’t end up at the same institution. So, Thomas was admitted to the Creative and Performing Arts High School and I went to Taylor Allderdice, where all of my siblings had gone for ninth through twelfth grade. Although we no longer hung out at school, we had almost daily phone conversations, and we continued to get together to pursue our mutual interests whenever we could.

Starting in January 1985, one of the things we would do together was go to these monthly comic book and movie conventions called Transfer, run by Bill Boichel.

Bill was involved with comic book fandom since the 1970's. He had come to Pittsburgh for college, and started working with the Pittsburgh Filmmakers, an organization that promoted and educated people in photography and filmmaking. Bill started his Transfer events as a way to merge his passion for film and comic books. They were our passions, too. So going to those monthly conventions, and staying for the movies afterwords, was a must.

Cable was relatively new, and none of us could afford a VCR, so getting to see flicks like THX-1138, Alphaville, Dementia 13 and Plan 9 From Outer-Space (among others) on a "big screen" was life changing.

We got to know Bill through these events, and he would invite us help break down the tables that collectable dealers would sell their comics from during the daytime hours of the Transfer, and replace them with chairs for the movie screenings that would take place in the same room afterwords.

It was work we did happily just to be a part of the event, but our labors were also spurred on by the extra incentive of some pizza, which we couldn't ignore as we would generally spend every dime we had on comics earlier in the day. The counter-cultural touchstones that we were introduced to thanks to these Transfer conventions were without a doubt "transformative."

Bill would go on to play an even bigger role in our lives starting in 1986 when he opened his store, BEM, on South avenue in Wilkinsburg. He took us in and gave us jobs sorting and stocking comics after store hours. There was more pizza, and Bill spun records while we worked.

It's hard to explain to kids now, who have nearly every single note ever recorded available to them via a simple Google search, how important it was to know someone who actually had a library of records like Bill did.

You couldn't just walk into a record store and say, "Good Sir, I'd like a copy of MC5's Kick Out the Jams, please" as that record was LONG out of print, along with hundreds of other classics that were under-pressed, poorly distributed and forgotten. But Bill had an amazing collection, and educated us constantly.

Thom and I would spend as much time as we could there under Bill's expert tutelage, learning about comics, music, film and more. Bill is still at the forefront of the comic book world, you can see what he's up to at his store The Copacetic Comics Company, in fact, there's a section on his site devoted to BEM (It's under the Copacetic Universe sub-heading, look for BEM at the bottom of the page).

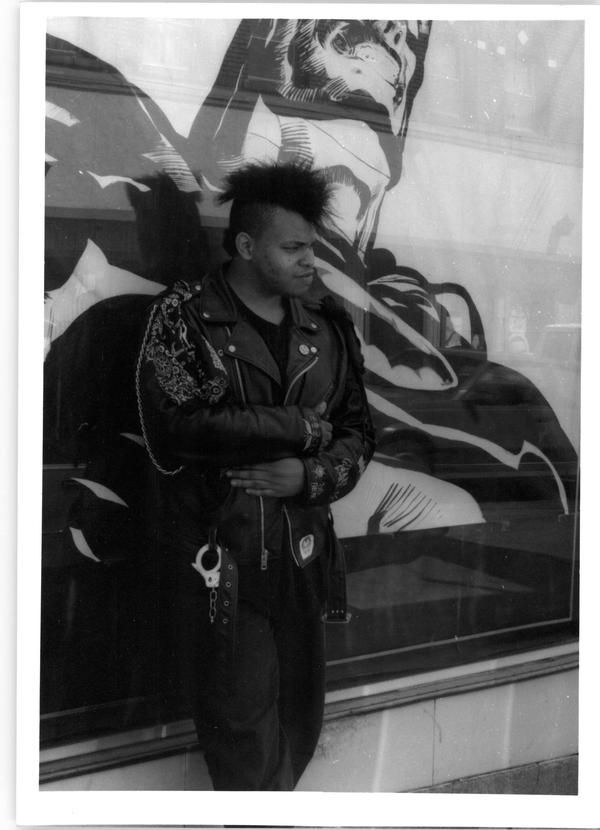

Through all of this "education", George Grant was like a big brother to me and Thom. The three of us went shopping for comics and records, played video games, watched that newfangled cable TV, and went to the latest movies together.

Many of the "Pop-Culture" benchmarks of that era had an influence on our creative endeavors. We discussed and debated the merits of it all, which led to us creating our own universe of characters and concepts. We all seemed to have endless energy and passion to create, and many hours were spent induging our imaginative expressions.

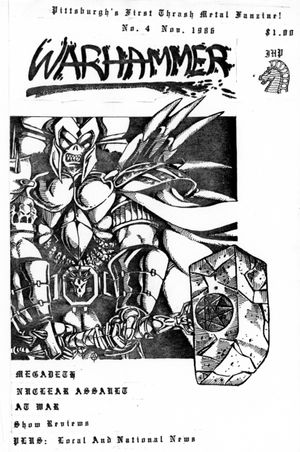

So when the idea of Warhammer came up, Thom was there and ready to collaborate.

His artwork is, of course, on the cover in the form of the Warhammer mascot.

It’s also on the titles for each section of the magazine...

He created the look of the warhammer-wielding warrior,

He created the look of the warhammer-wielding warrior,

whose “poser-crushing” hammer was emblazoned with our metal-punk-unity symbol.

This same character would end up on the flyer for the 1986 comeback show and the subsequent Warhammer benefit gigs.

Thomas was always full of ideas, as were George and I.

The three of us just wrote and drew and argued, spending hours with photocopiers and gluesticks putting together page after page of our xeroxed Frankenstein.

Most importantly we actually managed to see the process through.

Warhammer was poorly written, full of typos and paste-up blemishes.

It was cheaply reproduced and coarsely assembled, but we got it out there.

And Thom's artwork was so "professional" it helped people take Warhammer seriously.

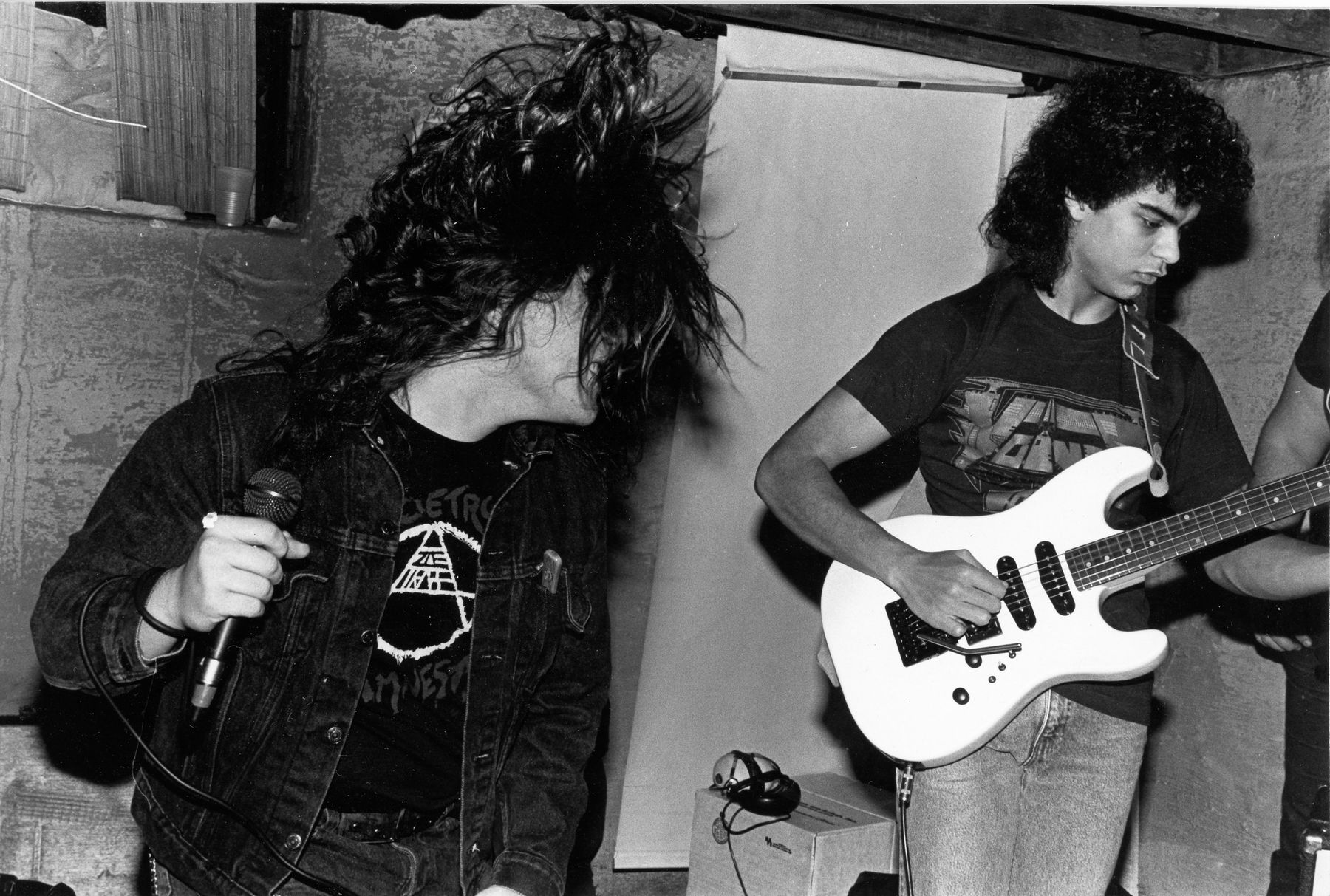

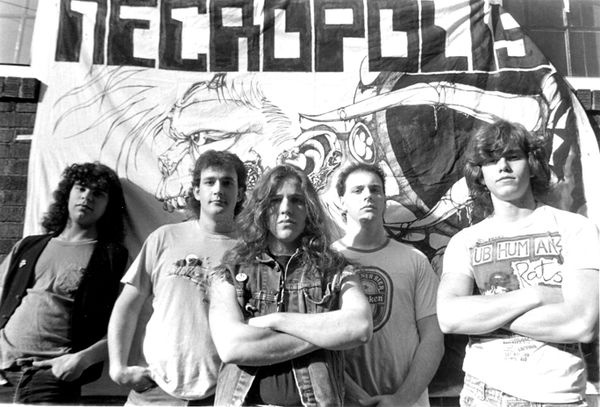

It was the same when Necropolis got rolling.

Thom wasn't writing the music or performing with us at the shows,

but he was often around at band practice and came to most of our gigs.

He was with us at our first apartment/practice space in the Strip District,

drawing away while we were creating our aural landscapes.

Thom was involved with just about everything we did as a group,

and it was never questioned that he was part of our “family”.

One of Thom's drawings graced the cover of the first Necropolis demo,

and then each of our subsequent releases.

His art was the focus of our three t-shirt designs.

As well as four of our sticker graphics.

Our live backdrop.

He was included in the photo shoot for our album, Breaking the Tradition,

as well as drawing the album cover.

He was part of the brotherhood and one of the few people along for the whole journey.

In fact, he introduced the band for our last live performance in August of 1989.

Simply stated, we were a family and Thomas was our brother.

We all contributed to Necropolis freely and passionately.

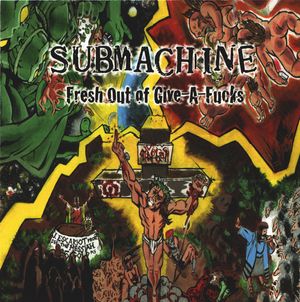

Thom‘s art is part of the Pittsburgh underground music scene to this day.

The bands that he has worked with are a veritable “Who’s Who” of steel town punk and metal: Shape of Rage,

Shape of Rage,

Eviction,

Doomwatch, Submachine,

Submachine, Battered Citizens,

Battered Citizens,

Wormhole,

Caustic Christ

...and many others.

...and many others.

Thom's artwork is still as vibrant and imaginative as it was when we first met back in the sixth grade,

and so many of Pittsburgh's underground bands have had the thrill of seeing his graphic creations associated with their musical endeavors.

But it all started here, in the City of the Dead...

- Spahr Schmitt