***IF READING ON A SMARTPHONE USE “LANDSCAPE” FORMAT FOR BEST RESULTS***

as hazily recalled by Spahr Schmitt

The origins of Necropolis begin with founding member George Grant...

George grew up playing music with neighborhood friends in the Wilkinsburg borough just beyond the east side of the Pittsburgh city limits. My oldest brother, John, and his wife Pattie, moved onto Marlboro street in the neighborhood, and we spent a good bit of time visiting.

My sister Scheri and her friends caught the attention of George and his buddies, which led to me hanging around a lot. Those guys gave me an education in hard rock and heavy metal like AC/DC, Rush, Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, and more. My sister and George became a couple, and then he really began to expand my musical education, even as his was diversifying, as well.

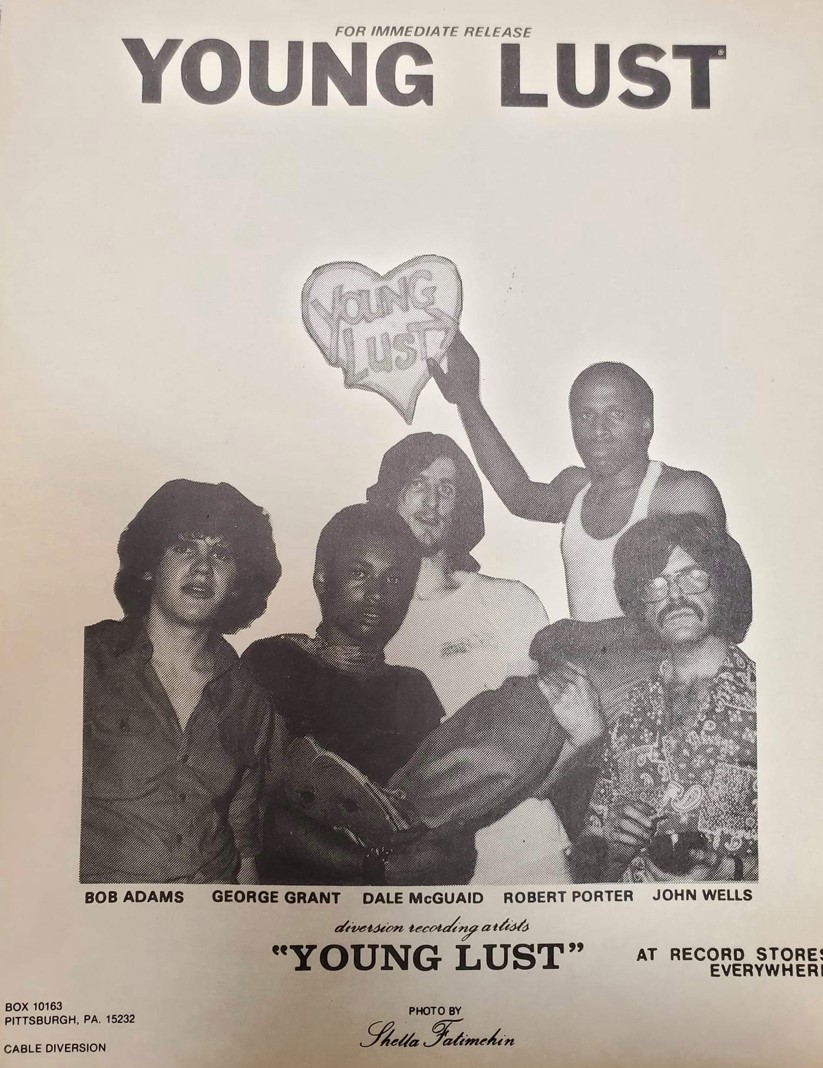

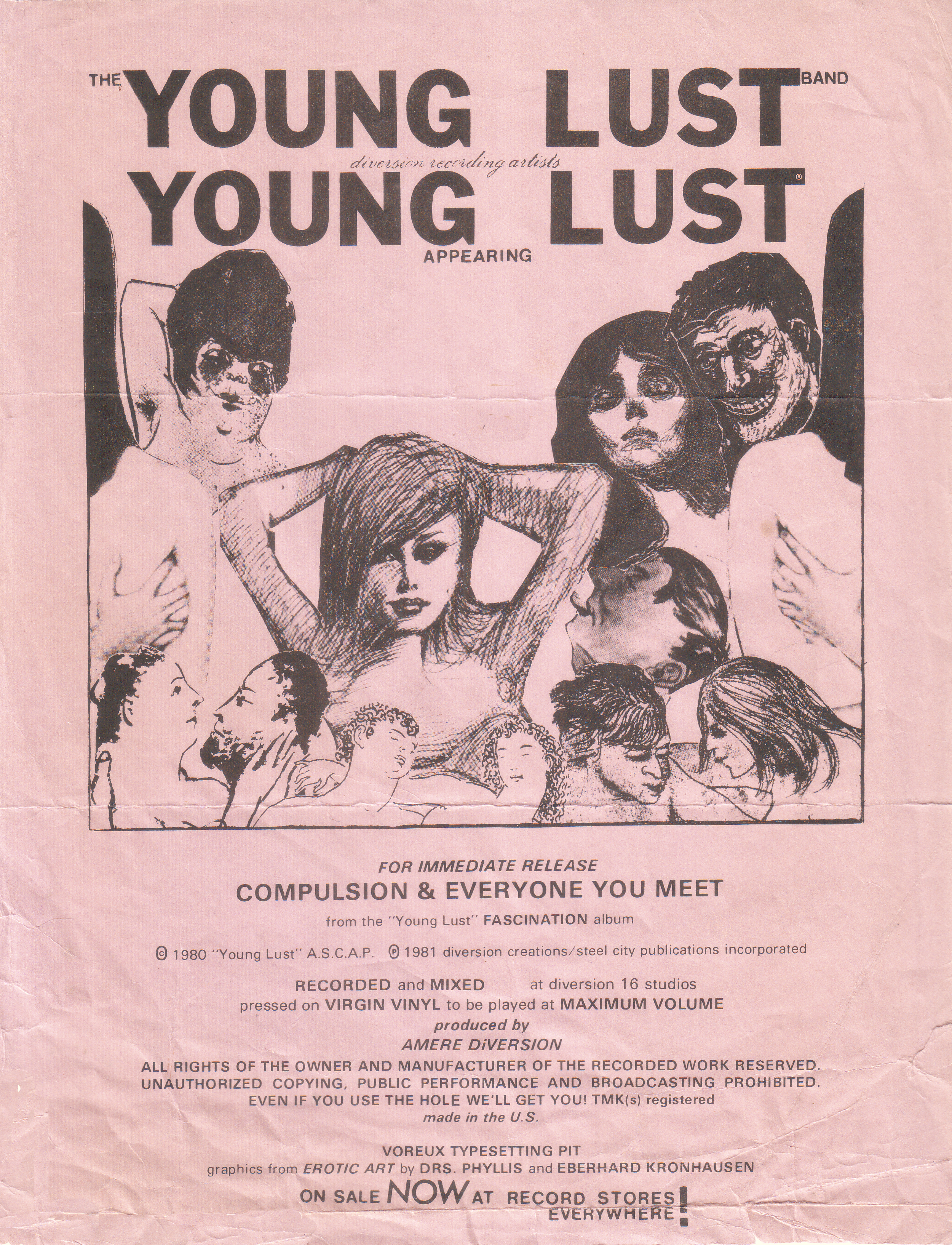

In his late teen years, George landed a gig playing bass in Bobby Porter’s band, Young Lust. In 1981 they released a vinyl 7-inch single featuring the songs “Compulsion” and “Everyone You Meet.” That made him the the first person I personally knew who appeared on an actual vinyl record - nearly unfathomable for my 12-year-old brain.

Shortly after the single was released, George left the group. He would soon re-emerge playing guitar for a punk band called Flak. This is 1984, and George began introducing me to Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys, and a myriad of other punk bands, including the Misfits, and their singer Glenn Danzig’s latest band, Samhain. Flak would go on to open for Samhain at the end of that year, at the infamous Electric Banana.

Around the same time, I was attempting to buy Man-O-War’s “Into Glory Ride” at local indie-music haven, Eide’s Comics & Records. The record counter clerk, Rob Tabachka, instead convinced me to buy a record I had never heard of. He told me that it was “the hottest thing in the underground,” Metallica’s “Kill 'em All”.

I took the cassette home and gave it the first spin... “Hit The Lights” got me a little wide-eyed, but it was the second track, “The Four Horsemen”, that made me sit up and take notice.

Specifically, it was the middle section of the song. The great tempo-change that transforms the song from its forebearer, “The Mechanix”, while arguably creating the blueprint for all "left-turn" rhythm changes, one of the key elements of thrash metal.

I stopped the tape and rewound it, played it again in awe, then rewound it and called George, because I HAD to play it for him as soon as possible. Upon hearing it, even over the phone, he simply said “bring that to my house tomorrow.” It was clear that this was no ordinary Heavy Metal album.

A short time later, Metallica released a new album, “Ride the Lightning”. I bought it immediately and it was a game changer. In less than a year, they had refined their approach, polishing their playing and production, intensifying the sound and style into something truly new.

Flak had disintegrated, but George was starting to conceive of a sound for a new project. One of his old Young Lust band-mates, Bob Adams, had confided that the name Necropolis would be great for a metal band. George started telling me that he wanted to put a band together that had the elements of Heavy Metal that we loved, combined with the ferocity of the Punk and Hardcore bands we were also inspired by.

He had also begun getting me into “Over-21” shows at the Electric Banana as his “little brother-in-law”, a slight fib, as he and my sister had been living together for a year or two by this point. So, it's 1985 and I’m seeing Samhain, COC, DRI, GBH etc. in person, which begins to tear down the walls between performer and audience for me, as the Banana didn’t even have a stage yet, just a drum riser. My 15-year-old self was standing on the same floor just a few inches away from Glenn Danzig, screaming along to all of the classic songs on "Initium."

I was falling in love with underground music.

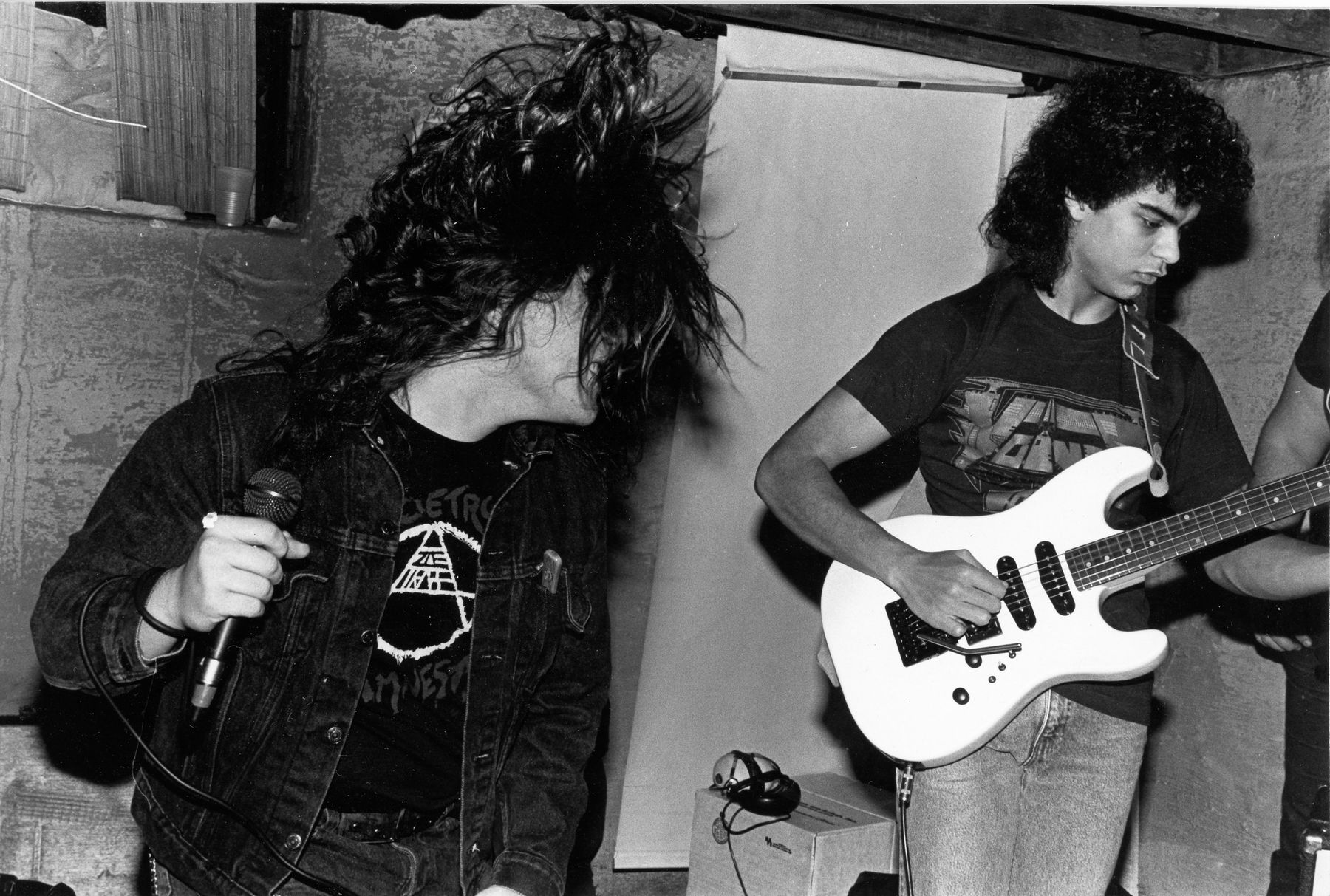

But Necropolis was still congealing in George’s brain. Around the same time, a few high school buddies of mine, guitarist Mark Crysanti and drummer Bill Wasiluski, we’re jamming in Bill’s basement with bass player Jimbo Freis. Mark had been trying to persuade me to sing for them, so I told George about it. Introductions were made, and before you know it, the boys started jamming on “Highway Star,” inspired by Metal Church’s souped-up rendition. You see, the other guys weren’t quite ready to glimpse the future that Metallica had convinced George and me of, so we were finding common ground.

At this point though, George was intending to sing and play guitar, so I was just a liaison and sidekick. Eventually, when George attempted to play guitar and sing, he struggled. The whole “rub your stomach while patting your head” thing would require a bit more practice. He was on the spot, and always being a generous friend to me, he looked my way and said, “you sing,” and that was it.

We put together a set's-worth of originals along with a few covers. Mark decided the style wasn't for him and departed. The rest of us would play just one house party back on Marlboro street, and then dissolve.

But Necropolis was born.

So, now the search was on to find some more like-minded individuals. Preferably people from the underground music scene, but that was proving to be difficult.

Most of the people on the punk scene detested Heavy Metal and it’s fantasy trappings, rock star clichés and Spinal Tap-esque presentations. At the same time, most of the metal people we knew thought Metallica was far too extreme.

By this point, we were listening to Slayer, Megadeth, Voivod, Anthrax, and the rest of the then burgeoning thrash metal scene. Even though it was in its infancy, it seemed like new bands were debuting vital albums every week. It was really an exciting time, although finding musicians who felt the same way in Pittsburgh was nearly impossible.

One day at high school, a punk friend of mine mentioned that there was a new kid in class who had moved from California and was into all of the bands I was listening to. His name was Jesse Michaels, and he had been banished to Pittsburgh to live with his mom because he was acting out a bit too much back in Berkeley. Sure enough, he had not only heard of the bands that we were listening to, he’d actually been to the Stone in San Francisco and seen Exodus, the Possessed, and others! And, he played drums!

I arranged an audition, and we ended up in Jesse‘s mom's basement. His drums, a six-piece kit with three rack toms and a floor tom, were covered with a blanket. Jesse explained that this was to keep the noise down while he played, as they lived in a row house with neighbors on each side. We didn’t bring any actual instruments to actually "jam", George just wanted to meet Jesse and find out if he was full of shit.

At that time, there were plenty of drummers who were competent players but most seemed to struggle when it came to playing that fast, hard-core-punk-style drumbeat.

Jesse had it down, so he was in.

When we returned to Jesse's basement to begin teaching him the songs, his drum kit had somehow shrunk to a four-piece with just one rack tom. He admitted that the blanket was really hiding the fact that he didn’t have the hardware to hold up the other drums! But it didn’t matter, he could play fast and understood what we were trying to accomplish, so that was that.

We started working in earnest, but we still needed a bass player. George soon found one in the form of Cam McDonald. Back in January of 1985 we had gone to Mancini’s Lounge in McKees Rocks to see Queensryche on “The Warning” tour. While waiting in line outside, we met Todd Porter and his friend, a fellow Art Institute of Pittsburgh student, Cam MacDonald. Cam came from upstate New York, and he also knew who Venom and COC were, along with all the other thrash metal bands we cherished. He brought his bass to Jesse‘s mom’s house and was able to pick up our songs pretty quickly. Now it was time to start putting the set together.

George was prolific as a songwriter. He seemed to be coming up with new ideas daily. We also started to develop a concept around the band name. George decided Necropolis was the post-apocalyptic aftermath of World War III, and the band were to be portrayed as survivalists. We would wear camouflage attire with bullet belts, etc. and the songs would have similar themes.

We would wear camouflage attire with bullet belts, etc. and the songs would have similar themes.

We also decided we wanted a symbol to bridge the gap that we saw narrowing between thrash metal and hardcore punk. The identifiable branding that seems ubiquitous in the modern era was hardly so in the mid-80s, and it was virtually nonexistent in the underground music scene. Even major music artists changed their logo from record to record, except of course for Iron Maiden who were demonstrating to us all the importance of creating a consistently identifiable “brand”. We merged the encircled “A” that represented anarchy, which was associated with punk rock, into the encircled upside down pentagram, the occult symbol which was becoming more and more connected to extreme metal. The resulting symbol created an identifiable trademark that we hoped would illustrate our desire to unite the two disparate sects of underground music fans whom we were courting.

George and I were living on the east end of Pittsburgh, at the border of Wilkinsburg and the city. There was a group of people that we hung out with, skaters and punk rockers.  People that I knew from school like Greg Gawlas, Neil Grant, Chris Garver, Shawn Slawson, Jon Dawson, Will Shepler and Chris Emerson, along with others from the neighborhood like Brian Cummings, Mike Sukel and Guy Asper.

People that I knew from school like Greg Gawlas, Neil Grant, Chris Garver, Shawn Slawson, Jon Dawson, Will Shepler and Chris Emerson, along with others from the neighborhood like Brian Cummings, Mike Sukel and Guy Asper.

A few of us brainstormed an end of summer picnic/gig/party at nearby Schenley Park that August. We rented a “pavilion”, which was a concrete pad with four posts supporting a metal roof over a few picnic tables and a lone light fixture. We unscrewed the lightbulb, screwed in a threaded socket-plug adapter, and powered a PA, and two amplifiers(?!) from that one socket.

Several bands played including an early version of Shape of Rage with Neil Grant, Greg Gawlas and Brian Cummings. If I remember correctly, their performance morphed into a sort of varied pick-up jam session with Mike Sukel and Chris Garver playing bass, Will Shepler and Chris Emerson drumming and Guy Asper singing, along with others. Shawn Slawson made his vocal debut performing an improv number called “Spike Is God” (a far cry from his future voice in Me First and the Gimme Gimmes). Eventually Jesse, Cam, George and I introduced Necropolis to the gang. It went over well enough for George to book us a gig at the Electric Banana that November.

So, we were ready for our first real performance. We advertised the show with the words "thrash metal" across the top of the flyer. To our knowledge, we were the first Pittsburgh area band to promote itself as part of the steadily growing thrash metal genre.

So, we were ready for our first real performance. We advertised the show with the words "thrash metal" across the top of the flyer. To our knowledge, we were the first Pittsburgh area band to promote itself as part of the steadily growing thrash metal genre.

We continued to learn songs for the set. George had written A number of original tunes, which we complemented with covers of Slayer (“Die by the Sword”), Venom (“1000 Days in Sodom”), Black Sabbath ("N.I.B.”) and The Misfits (“All Hell Breaks Loose”). The show was to be November 10, 1985. Now I would be the one holding the microphone standing on the floor facing the crowd.

It was a mix of Electric Banana regulars and underground metal fanatics looking for a local answer to the growing national trend of rougher, faster, more aggressive bands. We had a vision of the type of show we wanted to put on, but we didn’t have any money to speak of. Still, we had our heroes to borrow from, and we had our concept: the post apocalyptic "necropolis" where zombie soldiers fought an interminable war, forced to live the horror of the battlefield for eternity. So we took two sheets of plywood and painted our mascots onto them. Skeleton soldiers with machine guns and spiked army helmets, which we named Ed and Fred (from the city of the dead, naturally).

We had a vision of the type of show we wanted to put on, but we didn’t have any money to speak of. Still, we had our heroes to borrow from, and we had our concept: the post apocalyptic "necropolis" where zombie soldiers fought an interminable war, forced to live the horror of the battlefield for eternity. So we took two sheets of plywood and painted our mascots onto them. Skeleton soldiers with machine guns and spiked army helmets, which we named Ed and Fred (from the city of the dead, naturally).

We also got some dry ice, not a fog machine mind you, but actual dry ice, which we dropped into buckets of water hidden behind Ed and Fred. The resulting "fog" covered the floor around our ankles, and not much more (Electric Banana regular Tom Corman had a field day stomping at the creeping mist).

Our visuals may have been a ridiculous sight, but our performance went over well enough, despite other hilarious miscues. Fairly early in the set, Jesse started screaming my name loudly, desperately trying to get my attention. He wanted me to stall the next song because the mallet on his bass drum pedal had come loose and had flown off during the previous song! There were several minutes of confusion while he scrambled to find the beater and reattach it. I blathered on nervously, as I did all night.

There were other standard "first show" train-wrecks, like tuning issues and other equipment malfunctions. Still, the band was applauded, in spite of it all. It was three weeks before my 16th birthday, and although I wouldn’t get a drivers license for a few more years, I had just been given the greatest gift of freedom I would come to know.

In the aftermath of the gig, George’s frustration with the unprofessional, haphazard performance led him to seek out other musicians. For a while, from December into January, we played with another drummer named Steve, a bass player named Neil (who looked an awful lot like Neil from the Young Ones) and a guitarist named Karl Franklin. He was around my age and was quite a brilliant player (and still is - Check out what he’s up to HERE). We would take these long journeys out in the sticks to a house that the drummer was rehabbing. There we would woodshed for hours. The end result was turning into something, but it wasn’t the thrash metal sound we set out to achieve. I had to tell George my misgivings. At first he didn’t agree, but after a little personal reflection, he came around to my point of view. So we parted ways with that line-up.

We auditioned a lot of other people. Some notable names from the Pittsburgh scene including Ron Volpe, Steve Delach, Bill Turney, Ernie Bullard, to name a few. We just couldn’t find the right formula. This led us back to Jesse‘s basement where we ended up auditioning one of my high school friends.

Jon Dawson was a guitar player, and he had been playing with his neighbor Will Shepler (later of Circus of Death and eventually Agnostic Front & Madball) in a hardcore band called Child Labor. Jon had been nursing a broken leg he had gotten skateboarding on Will’s backyard half-pipe that summer. Being stuck in a full leg cast left him a lot of time to practice his guitar playing, but George was our guitar player, so Jon borrowed Chris Garver’s bass and came down to try out for Necropolis.

Coincidentally, George had met another guitarist, Ray Moretti (later of Disturbance), and invited him down to the basement that day to see what we had going on. Ray brought his Marshall half-stack and Gibson Explorer. After Dawson’s bass audition, Jon asked Ray if he could play his axe. While George and I bullshitted with Ray, Jon was noodling around on Ray's Gibson Explorer. At one point Moretti looked at George and me and said, “I don’t know why you’re trying this guy out on bass, he really knows his scales!” That he did, but George wasn’t quite ready to give up playing the six-stringer.

One day he showed me a set of lyrics for a song that he had written the night before called “Masquerade”. Clearly, he’d been having some fun with a thesaurus. But when he attempted to play the music for me, he had forgotten the riffs! Being an acolyte of the great Paul Baloff of Exodus, I started to read the lyrics with inspiration from Paul’s cadence and inflection. Think “Loki’s pets his little children, deadly every time!” if you know the Exodus song “Piranha”. As I began to improvise my vocal for the chorus, George followed me on the guitar. The result was the funky riff that is the backbone of the track. George plugged his guitar right into his cassette deck and recorded the guitar parts. We knew we were onto something and he wasn't going to chance forgetting that riff.

Meanwhile Jesse’s personal issues kept us from practicing regularly. Our neighborhood buddies Neal Grant and Greg Gawlas told us about another drummer. He knew how to play hard-core, but was also into metal. His name was Greg Mairs. He didn’t live close by, and his dad wasn’t really sure about his son being in a band. But I kept calling him and eventually he started to play with us.

Greg, George and I were getting the songs together in George's living room on East End avenue in Wilkinsburg. George was chomping at the bit to record something, so he scraped some money together and we went into a small studio in Duquesne, PA, called Sound Images. George and Greg cut bass and drum tracks, but when it was time to start recording guitars, the engineer, Al Pusaric, suggested we use his Rockman guitar preamps to go directly into the soundboard, saving the need for amps and microphones.

Greg, George and I were getting the songs together in George's living room on East End avenue in Wilkinsburg. George was chomping at the bit to record something, so he scraped some money together and we went into a small studio in Duquesne, PA, called Sound Images. George and Greg cut bass and drum tracks, but when it was time to start recording guitars, the engineer, Al Pusaric, suggested we use his Rockman guitar preamps to go directly into the soundboard, saving the need for amps and microphones.

For those who don’t remember, the Rockman was designed by Boston’s Tom Scholz as an electric guitar player’s answer to Sony‘s Walkman. It was a little guitar preamp that you could plug a pair of headphones into and practice without the use of an amplifier and speaker. Unfortunately, the guitar tone sounded like Tom Scholz' sound in his band Boston - heavily processed and very 1980s. Being a bit naïve and at the same time swept up in the novelty of the new technology, we agreed to use the Rockman. But soon we ran out of money for the sessions, and so recording at Sound Images was put on hold.

In the meantime,  we decided to scrape our pennies together and rent a four-track recorder to finish the recording ourselves. We could take our instrumental rhythm tracks we had on a cassette from Sound Images and then overdub leads and vocals on our own in George's living room for a fraction of the cost of studio time.

we decided to scrape our pennies together and rent a four-track recorder to finish the recording ourselves. We could take our instrumental rhythm tracks we had on a cassette from Sound Images and then overdub leads and vocals on our own in George's living room for a fraction of the cost of studio time.

When I told Jon Dawson about our weekend plans, he asked if he could help. He came over to George’s place and was a real contributor to the process, eventually cutting some guitar leads. During a break, he asked if he could record an instrumental composition of his own. He laid down a guitar piece, then a complementary part and finally, a lead. George picked up the bass guitar and played the progressions. The track would later be titled “Masque of the Red Death” at George’s suggestion, but Jon changed it to “Minuet of the Red Death.” His playing was sharp and his writing was polished, so with that, Jon was now a member of Necropolis.

We spent some more time experimenting with our limited equipment and the bass and drum tracks we laid down at Sound Images. The result was a demo we named "F.I.S.T." after one of our songs from that era. We did promote it a bit in the early issues of our fanzine, Warhammer, but we never actually released the recording. In the end, we went back to Al’s in Duquesne, and George, Jon and I cut leads and vocals, so that recording was finished as well.

Even though we were finishing the session, we hadn’t seen Greg in some time. He had left his drum kit at George’s place where we rehearsed. We noticed that the synthetic red “leather” material that covered the drum shells was ripped and peeling in some places. George decided we should apply our post apocalyptic survivalist theme to the drum kit, so we got some camouflage material, took the hardware off of the drum shells, stripped away the old red leatherette, and glued the camouflage material to the drums, all without ever asking Greg’s permission. Quite a leap on our part. We waited, and waited, but in the end, Greg never made it back to the band. He did eventually come get his drums and was a little shocked to discover the new camouflage finish on his kit, but he took it in stride. He soon resurfaced a short time later drumming for Pittsburgh hard-core legends Battered Citizens, and has been a fixture on the local punk scene ever since, drumming for Submachine, Caustic Christ and Killer of Sheep, to name a few.

Although we recruited a new drummer and guitar player, we only rehearsed a couple of times. It seemed that Necropolis was floundering.

Meanwhile, Jon Dawson started another band, Screaming Outlash.

Our one-time drummer, Jesse Michaels, was the singer, and our friends Mike Sukel (bass), Greg Gawlas (guitar) and Chris Emerson (drums) finished out the lineup.

Our one-time drummer, Jesse Michaels, was the singer, and our friends Mike Sukel (bass), Greg Gawlas (guitar) and Chris Emerson (drums) finished out the lineup.

They played a show at the new Shady Skate‘s location at 7501 Penn Ave. It was July 24, 1986. The songs were aggressive and thrashy as well as punky and melodic. Jesse had crafted some great hooks and lyrics, while Jon and Chris were growing exponentially in their musicianship. There was some real talent starting to emerge.

Screaming Outlash dissolved shortly afterwards. Jesse went back to California at the end of the summer, and soon started Operation Ivy - his story is pretty well documented from there.

But here in Pittsburgh, George saw an opportunity and asked Jon and Chris to join us in Necropolis, which they did.

We got to work rehearsing, and with two permanent members solidifying the band, the gestational period was over - the dream was coming to life...